I carried the title of “Architect” after a few years being a developer. At the time, it mostly meant being the person with the technical answers, the one who could navigate frameworks, design APIs, draw the system diagrams and guide developers. And while that work was valuable, I now realize that it only scratched the surface of what an architect’s role really is.

Over the last decade or so I’ve started to understand what it means to be an architect in practice and mindset. That understanding came gradually, through experience, missteps, and the growing realization that architecture is about far more than just technology.

One book that profoundly influenced that shift in perspective is The Art of Systems Architecting by Mark Maier and Eberhardt Rechtin. I read it years ago, and its insights continue to resonate. It explores how to think, frame problems, communicate with intent, and make decisions when certainty is in short supply.

This blog is a reflection on how I’ve come to embrace what software architecture means to me. And while I have deep respect for today’s technology architects who bring mastery over cloud platforms, distributed systems, and performance engineering I believe there’s a meaningful distinction between engineering and architecture.

Engineering is about optimizing what’s known. Architecture is often about shaping what’s not. What follows is a set of ideas, shaped by practice, that have helped me grow into the role and stay grounded in it.

What It Meant Then, What It Means Now

Long before software systems, the idea of an architect carried weight, not just as a designer of structures, but as someone entrusted with balancing form, function, and purpose. One of the earliest and most enduring views of the architect’s role comes from Vitruvius, the Roman architect, engineer and writer who likely lived during the time of Julius Caesar.

To Vitruvius, an architect wasn’t defined solely by technical capability. Instead, he painted a picture of someone with broad curiosity and interdisciplinary insight — someone who understood geometry and music, philosophy and astronomy, law and medicine. The architect, in his view, needed to be both deeply skilled and widely informed. A technician, yes — but also a thinker, a synthesizer, and a student of the world.

Reading that today, it’s striking how much still applies. In software architecture, we may not need to study the heavens nor memorize classical music, but we do need to integrate technical, human, and contextual considerations. We need to understand constraints and opportunities not just in the code, but in the business domain, the organizational landscape, and the environment in which the system will live.

In that sense, the modern architect is a polymath of sorts. Someone who bridges the measurable with the immeasurable, the analytical with the intuitive. Someone who can connect dots others may not see

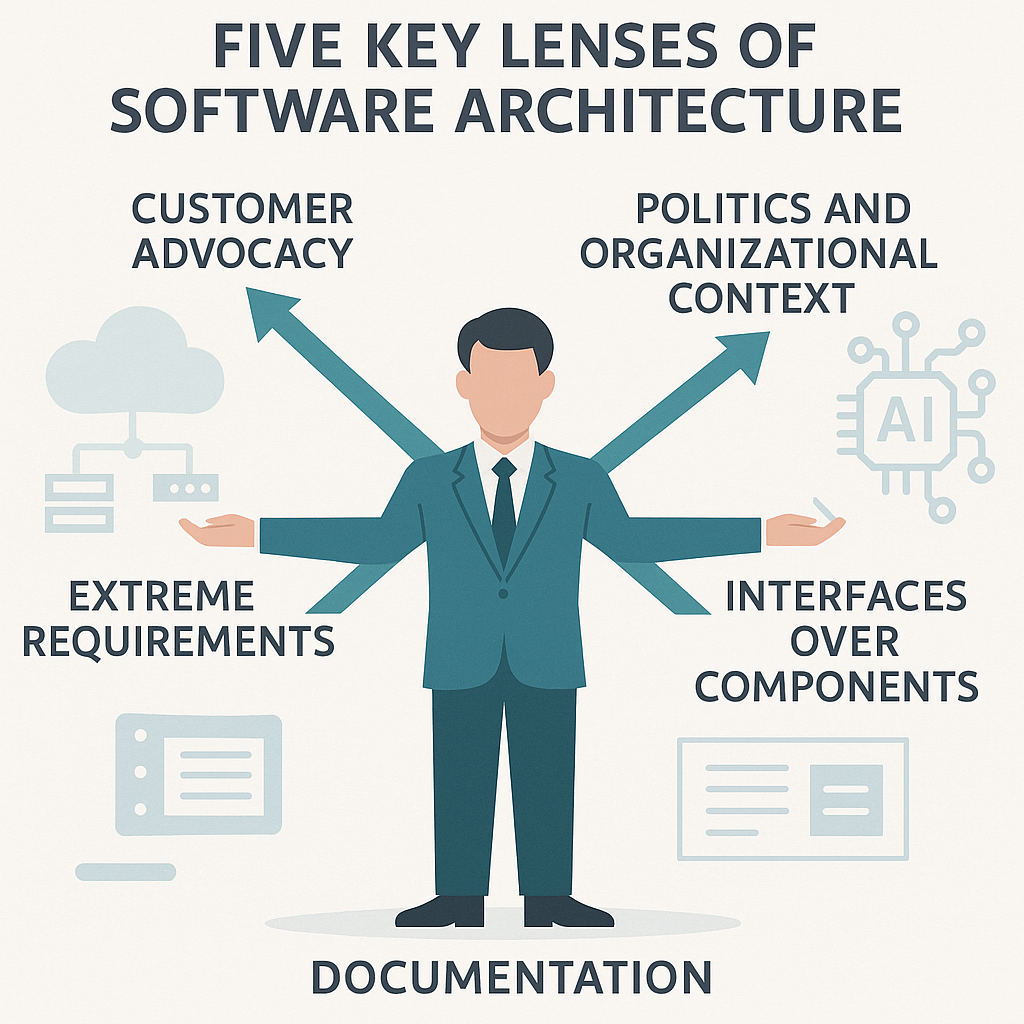

Reflecting on my own experiences, I believe the following five lenses help illuminate what it truly means to be an architect. These perspectives have only grown more relevant in a world where systems are increasingly distributed, cloud-native, and data-driven — where AI, LLMs, and agentic workflows are reshaping how we think about functionality, scale, and autonomy. In this era of accelerated innovation, architecture is no longer just about building something that works — it’s about orchestrating solutions that adapt, integrate, and evolve across a constantly shifting landscape. These lenses have helped me stay grounded while navigating that complexity.

The Architect Is an Agent of the Customer — Not the Builder

One of the most important shifts in thinking that shaped me as an architect was recognizing who I really represent. Early on, it’s easy to assume that as part of a delivery or engineering organization, your job is to align with the builders to make sure the solution is technically feasible, clean, and implementable. And while that’s certainly part of the role, it’s not the whole picture.

Over time, I realized that my primary responsibility lies with the customer in the broader sense of advocating for the person or group the system is ultimately meant to serve. That means stepping back from the mindset of “what can we build?” and instead asking “what should we build?” Sometimes that means questioning assumptions, revisiting scope, or even rethinking the problem itself.

There have been moments in my work where the engineering team was ready to move forward with a well-scoped implementation, but it was clear the underlying requirements were still evolving or worse, misaligned with what the stakeholders truly needed. It’s in those moments that an architect needs to pause, engage with the customer, and co-define the vision and shape requirements.

This role can feel uncomfortable. It requires pushing back, asking hard questions, and being okay with ambiguity.

I’ve learned that architects must be willing to engage early, when things are still fuzzy. Waiting for complete and consistent requirements may feel safer, but that’s not architecting that’s building. The value lies in navigating the uncertainty, guiding the process of discovery, and aligning what’s technically possible with what’s truly needed.

Sometimes it means taking positions that may not align with delivery convenience. If the job is to create systems that matter, systems that deliver value, evolve with purpose, and reflect the priorities of the people they’re meant to serve then the architect must sit on the side of the customer. Even when it’s uncomfortable.

Architecture and Politics Are Intertwined

One of the more sobering lessons I’ve learned over the years is that architecture doesn’t live in a vacuum. The success of an architectural decision is rarely determined solely by its technical merit. Often, it’s shaped and constrained by the political landscape surrounding it.

In the early stages of my career, I believed that the best ideas would naturally rise to the top. If something was efficient, scalable, and well-designed, it would get implemented. Over time, I realized that wasn’t always the case. I’ve seen well-thought-out solutions get set aside because they didn’t align with organizational politics or the priorities of an influential stakeholder. I’ve also seen imperfect solutions succeed because they had the right backing, fit neatly into existing roadmaps, or simply arrived at the right time.

Architecture, I’ve come to see, exists within a political context. There are trade-offs being made constantly, often behind the scenes between teams, across departments, and up and down management layers. Budget allocations, shifting goals, risk appetites, and even interpersonal dynamics can influence which ideas move forward and which ones stall.

As architects, we can’t afford to be blind to this reality. It means we stay aware of the environment we’re operating in. The job is as much about listening and reading the room as it is about designing. It helps to work closely with program managers or leaders who understand the internal landscape and can offer guidance when things get political.

There are times when we’ve had to accept less-than-ideal decisions due to time, budget, or alignment constraints. Writing down why those decisions were made, and how we might mitigate them later, has helped prevent confusion down the line. It’s also a subtle acknowledgment that architecture is about navigating constraints and making forward progress without losing sight of the bigger picture.

Architecture and Extreme requirements

One of the lessons I’ve learned in architecture is how to approach extreme requirements. The kind that are unusually demanding, risky, or ambitious. These often appear as aspirational goals early in a project: ultra-high availability, near-instant response times, or handling massive scale from day one.

Earlier in my career, I treated these requirements as non-negotiable. If they showed up in a document or were mentioned by a stakeholder, I assumed they needed to be engineered around no matter what. But over time, I began to see a crucial distinction: an extreme requirement only makes sense if it is truly intrinsic to the system’s design philosophy. It must justify its presence by aligning directly with the system’s purpose and validating the decisions it makes.

This distinction matters, especially in modern environments where both time and resources are constrained. Designing for theoretical extremes that don’t align with actual usage often leads to unnecessary complexity and brittle systems. Teams burn cycles solving problems that may never materialize, while losing focus on what really matters.

But when an extreme requirement is fundamental to the system’s identity, it must be treated as a core design driver. For example, a trading system cannot compromise on latency. A medical diagnostic platform must prioritize explain-ability and auditability. In these cases, architecture should not work around the extreme; it should work because of it.

What I’ve found helpful is not just accepting such requirements at face value but questioning their role early in the process. Is this truly critical? Does it define the success of the system? Can it be measured? What are the implications in terms of cost, time, and operational complexity? If the answers point to a clear need, then that requirement deserves to sit at the center of the architecture.

Extreme requirements aren’t inherently wrong; they must be earned. When they are essential, they clarify purpose and sharpen design choices. When they’re not, they quietly dilute focus and derail delivery. Knowing the difference is one of the responsibilities of an architect.

The Greatest Leverage in Architecting Is at Its Interfaces

Over time, I’ve come to appreciate that interfaces, not components, are where the real leverage lies in architecture. It’s easy to get drawn into the internals of systems: optimizing services, selecting design patterns, refining data models. But the truth is, the make-or-break moments often happen at the edges where systems interact with each other.

I’ve seen technically solid components falter because the interfaces between them weren’t designed with enough care. Sometimes it was due to incomplete understanding of what information needed to be exchanged. Other times, it was the lack of clarity around how to handle failures or scale under load. Interfaces are where assumptions tend to hide and where they inevitably get exposed.

What I’ve realized irrespective of the technology, whether the integration is batch, event-driven, API-based, or messaging-based; the critical differentiator is the quality of the interface design. The completeness and clarity of the contract. A robust interface considers the full lifecycle of the exchange: authentication and authorization, service discovery, versioning, error handling, timeouts, retries, failure modes, monitoring, and performance under stress.

When these aspects are thought through and designed for, integration becomes predictable. When they’re overlooked, teams spend cycles debugging issues that could have been avoided with clearer boundaries and better alignment.

One practice I’ve found consistently valuable is asking; what’s this interface supposed to do? What are its guarantees? What happens when something goes wrong? If the downstream system can’t answer those questions confidently, then the interface isn’t ready.

Well-designed interfaces reduce friction. They minimize surprises. And they become enablers of change — because when interfaces are stable and well-defined, the systems behind them can evolve independently. That’s the kind of leverage that makes architecture truly impactful and architects can make their value obvious.

Documenting Architectures: Clarity Over Completeness

One of the quieter but most critical responsibilities of an architect is to document the architecture to create shared understanding. Over time, I’ve come to see that an architect’s job is as much about architecture as it is about being the architecture’s chief communicator. You can design the most elegant system in your head, but if others can’t see it, grasp it, and build from it, it doesn’t really exist.

Good documentation is finding the right level of abstraction for the audience, the right visual to carry the concept, and the right notation to eliminate ambiguity. Visuals matter, but notations matter even more. A polished diagram might impress, but consistent symbols and terminology are what make it usable, especially when people come back to it months later trying to understand what was decided and why.

Another thing I’ve learned is that no single view captures everything. Architecture lives across perspectives: logical flows, component interactions, deployment topologies, data exchanges, failure modes, security boundaries. Trying to cram all of that into one diagram does more harm than good. Instead, I try to create a set of complementary views each serving a different purpose but tied together with consistent language and assumptions.

And of course, the point isn’t just to draw diagrams. It’s to provoke questions, surface trade-offs, and create alignment. A well-structured architectural document should spark conversations. It should help new team members ramp up quickly, and provide continuity when people move on. It should be a living asset evolving with the system, not getting left behind as shelf-ware.

The more systems I’ve helped design, the more I’ve come to value the discipline of documentation. It’s not glamorous, but it’s essential. It’s what allows architecture to scale beyond the architect.

In conclusion — Modern Problems, Timeless Principles

Much of architecture is about listening carefully, clarifying intent, and reconciling competing perspectives. Looking back, I don’t remember the projects where I nailed the perfect data model or picked the optimal pattern. I remember the moments when a well-timed question reframed the problem. Or when a sketch on a whiteboard helped two teams finally see the same picture. Or when we revisited a decision months later and could trace exactly why we made it — and how to improve it now.

That, to me, is the real work of an architect.

And if anything, this work is becoming more relevant — not less — in the age of AI-powered systems. These solutions may rely on new tooling and techniques, but they are still bound by the same fundamentals: a clear business need, a finite budget, and real technical constraints. AI introduces new complexity — uncertainty, explain-ability, ethical considerations — but the architect’s role remains the same: to bring clarity, structure, and intent to that complexity.

The context has evolved, but the responsibility endures. Architecture still matters — perhaps now more than ever.